Rails and roots: BNSF’s start in Aurora, Illinois

By PAIGE ROMANOWSKI

Staff Writer

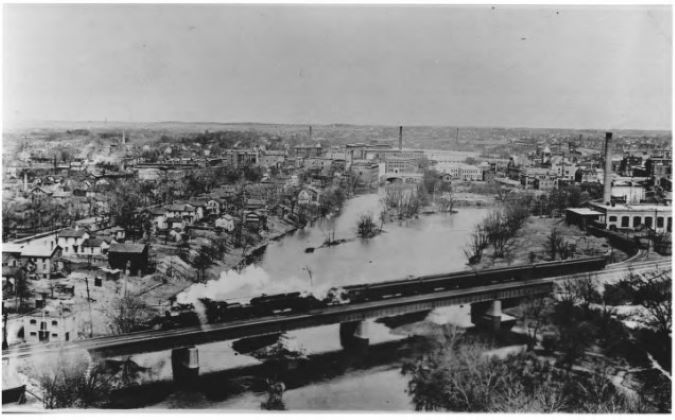

Aurora, Illinois, a western neighbor to Chicago, is where BNSF got its start 175 years ago. A short stretch of track set BNSF’s destiny into ‘loco-motion’ and grew over many decades into a network spanning 32,500 miles.

In 1849, the Illinois General Assembly chartered the Aurora Branch Line, a humble 12-mile section of track connecting Aurora to West Chicago, bringing these developing communities access to the city. A hodgepodge of borrowed equipment and secondhand steel tracks, the Aurora Branch Railroad pushed ahead and was the second railroad to serve Chicago.

A few years after the Aurora Branch’s beginning, investors realized that the line faced isolation amongst the rapid expansion of additional rail lines in the state and recognized the need to grow.

“The Aurora Branch had to expand itself or expand with another railroad to remain relevant,” Leo Phillipp, vice president of education and outreach at the Burlington Route Historical Society and former Burlington Northern Railroad employee, explained. “Investors asked to join the Galena and Chicago Union, but they [the Galena and Chicago] were not interested, pushing the Aurora Branch to expand. They chartered a new line to Mendota and the name changed to the Chicago and Aurora.”

The Chicago and Aurora would soon connect to the Illinois Central and from there the system quickly expanded. The Chicago and Aurora’s impressive growth caught the eye of John M. Forbes, an East Coast investor dedicated to building the Michigan Central to Chicago. With Boston money, it grew to become the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad (CB&Q or Burlington Route), stretching across Illinois to Peoria and Galesburg and ultimately the Mississippi River.

Moving agricultural products from the surrounding rural communities to Chicago and industrial products from the city back to the rural communities, the Burlington Route was an essential part of the Midwestern supply chain.

The CB&Q didn’t just move goods, it moved people too. During the Gilded Age, passengers from western communities could reach Chicago in just three hours compared with the traditional two-day trip on horseback.

“The Burlington Route had direct connection to the growing markets,” Phillipp said. “When industry and population grew, so did the rail traffic.”

Traffic on the original Aurora Branch grew dramatically and movement became constricted. Continuing their growth mindset, in May 1864 the CB&Q completed a direct rail line from Aurora to Chicago – making the original Aurora Branch an official branch line (a secondary line that connects to a main line).

Soon, two roundhouses were constructed to house, repair and direct the CB&Q’s fleet of steam locomotives. As locomotive technology evolved, diesel and car shops were built in Aurora to support the growing network.

Today, one of the two roundhouses is still standing and has been converted into a restaurant: Two Brothers.

“General Mills bought an idle factory on the branch line, and during the late 1960s and early 70s, local traffic increased from one train a day to four,” reminisced Phillipp. “I mean, what an accomplishment for CB&Q. Just across from General Mills was our competitor, the Chicago and Northwestern. The tie between Burlington and Aurora was completely symbiotic.”

At Aurora’s peak, the CB&Q employed more than 400 trainmen. Crews would service local routes for freight and passenger service across the western and southern suburbs of Chicago.

Today, that little branch is a triple track main line within modern day BNSF’s Chicagoland operations. Though Aurora is no longer a bustling hub for our operations, the town has never deviated from its agricultural and industrial freight roots.

“Our presence in Aurora has lessened as industry has moved away from the state, so today Aurora sees local traffic via customers and originating sand unit trains,” said Robert A. Della-Pietra, senior trainmaster in Aurora. “Day to day, we move unit trains carrying agricultural products and sand ‘Everywhere West.’”

Aurora’s Eola yard still functions as a freight yard and is the ending point of the Chicago Division’s commuter “racetrack,” giving way to the nickname for the Eola yard: “End of Line Aurora.” BNSF is proud to operate Metra lines through Chicagoland and continue the Burlington Route’s legacy passenger services in collaboration with Amtrak.

Though our freight operations in Aurora have slowed as neighboring communities have further developed, we are grateful to Aurora for our historic beginning and the 12-mile section of track that would birth a great company and change the trajectory of the Midwest and the American economy.